That first meeting was fraught with anxiety, I think for both of us. My Aunt Penny and Uncle Day and I tromped down the wide nursing home hallway, the tile floor glimmering in the florescent lighting. And then we were at the door. A narrow entry opened to nothing fancier than a hospital room, minus the paraphernalia. She sat in the corner on an easy chair, holding Baby.

I'd been warned about Baby. In her old age, Leona had taken to calling a small white teddy bear Baby. She wouldn't let go of it, and it doesn't take a brain surgeon to figure out what this is all about.

We went down to the cafeteria, with Baby of course. My missing grandmother, Baby on her lap, asked, "Why did you keep looking for me?"

"Because you're my grandmother and I've missed you all my life."

Five minutes later, "Why did you keep looking for me?"

Five minutes later, again.

I finally figured I wasn't addressing her real question of why. When she asked for the fifth or sixth time, I said, "Because you're my grandmother, and I love you."

She put Baby down and reached across the table to take my hands. "And I love you, too."

For the first time in a very long time, she let go of Baby. Uncle Dale captured the miracle on film. My missing grandmother had, for just a few moments, found relief from the pain over losing my mother.

She wasn't much help in sorting out the story, though. "One mustn't speak ill of the dead," she told me and clammed up, much like my old aunties--her sisters-in-law.

Penny tried to prod her into speaking about Isabella, but Leona stopped her. "Now, Penny, I've told you before. Granny Goodfellow did what she thought best at the time. And in the end that's all any of us can do."

Blow me away with a feather.

Between Penny and my mother this is what I had pieced together by the time I met Leona. Leona and Les were married the summer of 1927, childhood friends from two families who knew each other but didn't socialize. One was strict Protestant, the other nominal Catholics. One great-grandmother, Lucy May Bagley, pawned her pretty and costly purchases with my other great-grandmother, Isabella Stewart Goodfellow. They were neighbors, at one point living on the same street in Calgary, Alberta, in the same block, on the same side of the road. Sometimes Lucy May couldn't bring back the necessary cash to retrieve her precious purchases and lost them to Isabella. I didn't know growing up that my favorite bowl--a lovely large cut glass bowl we used for sugar--had actually been one of Lucy May's. Fred Bagley's Mountie pension and poorly-paid civil service job didn't allowed the Bagleys very many luxuries--and Lucy May apparently overspent her budget with some regularity. I suspect the arrangement between the two women spawned some level of resentment on Lucy May's part and disdain on Isabella's; and may have been the seed of disapproval from both families when Les and Leona unexpectedly married.

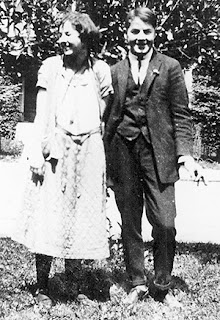

Between Penny and my mother this is what I had pieced together by the time I met Leona. Leona and Les were married the summer of 1927, childhood friends from two families who knew each other but didn't socialize. One was strict Protestant, the other nominal Catholics. One great-grandmother, Lucy May Bagley, pawned her pretty and costly purchases with my other great-grandmother, Isabella Stewart Goodfellow. They were neighbors, at one point living on the same street in Calgary, Alberta, in the same block, on the same side of the road. Sometimes Lucy May couldn't bring back the necessary cash to retrieve her precious purchases and lost them to Isabella. I didn't know growing up that my favorite bowl--a lovely large cut glass bowl we used for sugar--had actually been one of Lucy May's. Fred Bagley's Mountie pension and poorly-paid civil service job didn't allowed the Bagleys very many luxuries--and Lucy May apparently overspent her budget with some regularity. I suspect the arrangement between the two women spawned some level of resentment on Lucy May's part and disdain on Isabella's; and may have been the seed of disapproval from both families when Les and Leona unexpectedly married.Grandpa Les had been living in Vancouver BC for two or three years, working as a mechanic for Begbie Motor Company when Leona, two years older than him and a school teacher on the Alberta prairie, went to Vancouver for summer vacation. They married unexpectedly, and no one was pleased.

From her savings, Leona bought a house, but things seemed to unravel quickly. Within a few months she was pregnant, Les invited his best friend Phil to come live with them, and he fell in love with Marguerite. By the time Leona went into labor the first of October, 1828, Les was living with Marguerite and Phil was still in Leona's house. Leona had to call a taxi and get herself to the hospital. She got herself home, too, with Shirley Elizabeth Goodfellow, the spitting image of my handsome 1920's playboy grandfather.

I can well believe Leona was depressed. Married only fourteen months, home with a newborn, husband living with another woman, a stranger in her house...no means of income. Who wouldn't be? It seems she held out while her savings lasted--another year perhaps.

|

| Isabella Goodfellow Shirley Elizabeth Goodfellow |

Leona's story differs. She managed to get a job teaching school in Alberta, and arranged for Les' parents, Isabella and Walter Goodfellow, to leave Calgary and come live in Leona's Vancouver house and look after Shirley while Leona, after teaching the week, took the weekend train from Calgary to Vancouver, paying the Goodfellows for Shirley's care from her meager salary. A strenuous arrangement for sure--and one that abruptly stopped when Shirley was about eighteen months old. I can't even imagine the shock. The cruelty.

Les and Marguerite picked Leona up at the train station that weekend. Les put her into the backseat and told her she'd be allowed to see their daughter only briefly and for one last time. He and Marguerite would take her right back to the train depot. My grandmother was not even allowed to enter her own home or hold her own baby. She was forced to say goodbye from the doorway. The Goodfellows took Mum to Calgary to grow up as Betty--where she was never allowed to dilly dally after school lest her mother come and kidnap her.

By the time I finally met Leona in 1996, this is all that I'd pieced together. Penny and I didn't get much more out of her, however, and I went home just as curious but happy. I'd finally met her, and, no, Fred Bagley had not said, as rumored, "Come home but leave the brat behind."

Six months after meeting Leona, she fell and broke her hip. From her hospital bed, delirious with pain and in a morphine haze, she kept asking for me."Don't let them take the baby!" she cried when she saw me. "Brenda! Don't let them take the baby!" and she wept in grief so terrible it sent spasms rippling through my heart.

I gave her the teddy bear. "Here she is," I said, trying to comfort her. Baby wouldn't do. My missing grandmother wanted the real baby, she wanted my mother, and she kept crying and pleading, begging me. "They've taken the baby! They've taken her! PLEASE GET MY BABY!" She was 92 years old. All this had happened 64 years ago. Decades of suppressed pain exploded loose, tearing her apart, tearing me apart. And in that first hour, morphine weakening her guard, more of the story spilled out.

Leona never did understand why Phil was living with her and Les; or why he remained in the house after Les moved out. She had to feed him, do his laundry, fix his meals. She'd been beaten, she didn't know why. Her father had brought my mother a wicker baby buggy from Banff for her to sleep in. And for some bizarre reason, Isabella kept yanking Leona's wedding ring off (a ring she'd purchased for herself). One night, after Isabella had again tossed the ring into the trash, Leona snuck into the kitchen, retrieved the ring, and tucked it into the woven wicker of my mother's baby buggy.

"Why did you tuck your wedding ring into the baby buggy?" I asked when her sanity returned.

"I said that?" Leona asked in shock.

"Yes." When I pushed for a reason, she shrugged, bewildered.

"I don't know. I guess I just wanted it to be near the baby."

"Who beat you?"

"I told you this?" More shock.

"Yes. Who hurt you? Did my grandfather beat you?"

She wouldn't say. It wasn't nice to speak ill of the dead.

She died within a couple of months, and her painful secrets went with her. I'll never know what really happened. Except this. A terrible wrong was done.

Yet... Yet Leona's astonishing ability to endure and live with secret pain filled the enormous hole I once had. Informing me more fully of who I am. From her comes my own courage and fortitude and ability to endure and live beyond pain. Not as great as hers, not by a long shot, but nonetheless hard at times to bear. And here is my hope. Maybe, just maybe, maybe someday I'll find that I too am made of the stuff that can say, "So and so did their best, and in the end that's all any us can do."

By searching for Leona, I found Fred. And in searching for Fred, I found her. And in her, I found a measure of myself.

And somewhere in Vancouver BC Canada is a wicker baby buggy, forgotten in an old attic and or on sale in an antique shop, with a wedding ring hidden in the weft. If you find it, it belongs to my grandmother and tells a story that whispers and nags despite the secrets taken to the grave.