| Frederick Augustus Bagley Battleford, Saskatchwan, 1875 |

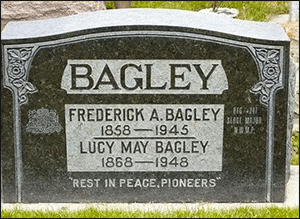

His daughter was a missing grandmother in my life—a woman who, it was said, abandoned my mother when she was six weeks old. Where Leona had gone or where she was, no one knew and none seemed to care. And while the judgment against her wasn’t particularly harsh (her actions explained away as depression and, after all, Granny Goodfellow, had been quick to step in and raise baby Betty), Leona’s father, my great-grandfather, came under a much harsher light. When Leona asked if she could leave her husband and come home, Frederick Augustus Bagley had apparently said, “Yes, but leave the brat behind.”

And so while I loved and missed my missing grandmother, and grew up yearning to find her, I secretly resented my great grandfather. After all, had he been a bit more understanding of whatever the plight may have been in 1928 my mother would have never been an orphan of sorts and my missing grandmother would not have gotten lost. Who was this man who thought my mother a brat? I didn’t care. I just wanted my grandmother.

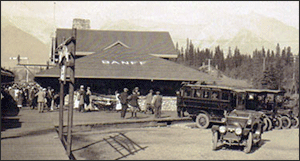

.png) I was fourteen when my family drove into Banff, AB, for the first time. I was sitting in the back seat, between my two sisters. I had a straight-on view as we came in—the Rockies climbing up the sky all around me, just ahead the stone bridge and stately old hospital. I scooted forward with an exuberance new to me. In my fourteen years we’d moved a lot; any sense of home had dissipated, leaving me with a feeling of transience. But driving into Banff I recognized home. Here, I belonged. Here were roots. Here was my energy source.

I was fourteen when my family drove into Banff, AB, for the first time. I was sitting in the back seat, between my two sisters. I had a straight-on view as we came in—the Rockies climbing up the sky all around me, just ahead the stone bridge and stately old hospital. I scooted forward with an exuberance new to me. In my fourteen years we’d moved a lot; any sense of home had dissipated, leaving me with a feeling of transience. But driving into Banff I recognized home. Here, I belonged. Here were roots. Here was my energy source. Why? I didn’t know.

|

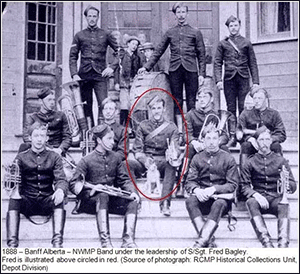

| First Mountie Detachment: 1896 |

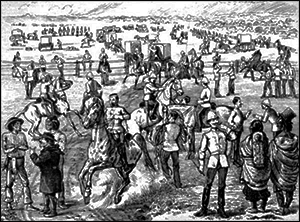

It was with great reluctance that I said goodbye to Banff, yet…in grade four, Miss Bilby had told us stories about growing up on a farm outside Regina, SK, and it took my breath to see the prairie unfold as we dropped down out of the Rockies to meet the plains. Was it her stories that made my spirits soar? That gave me that sense of recognition and delight? Perhaps. Yet I’d heard many stories of wondrous places that didn’t, when experiencing them for myself, evoke such a keen sense of connection. We passed Dead Man’s Flat and drove right into the lapping waves of an ocean of grass that in actuality was my great-grandfather’s country. I didn’t know he’d spent his life here, that he’d policed the thousands upon thousands of square miles of earth and sky so flat and far-reaching it boggled my mind. I didn’t know…yet I must have known. I was recognizing land I loved and didn’t know I missed. Perhaps this is why Miss Bilby’s stories had meant so much to me.

|

| Ft. Macleod AB |

Dad went over, I hid behind a bookcase; she was not my mother.

“Look! Here’s my grandfather! It has to be him. ‘Frederick Bagley, Crack-shot of the RCMP,’” she quoted and I came out from behind the bookcase.

“Your grandfather was a Mountie?” I asked, meeting his eyes and thinking he looked like a decent sort. Not the kind of guy who called his granddaughter a brat.

Mum headed for the cash register. I tore my eyes away from this man whose bloodline I carried and quickly trundled along behind , ears on high alert and wondering why I’d never been told this bit of information. A Mountie? I pictured of the red-tuniced men parading around on frisky horses in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

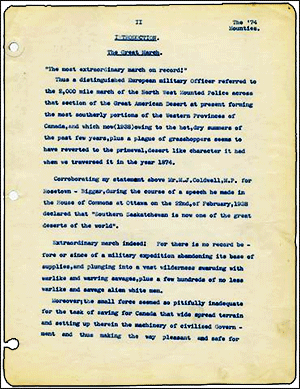

The long and short of the ensuing conversation at the cash register was that the curator was just then reading Fred Bagley’s diary, written when he’d crossed the prairies in 1874 as a fifteen-year-old kid. One year older than myself! His diary, however, was open only to family. So why give it to the museum? Mum patiently explained she was family. Didn’t matter. She still had to get permission from one of his three daughters, Kate, Leona, and Marian. [today you can read the diary for yourself by clicking on this link: https://albertaonrecord.ca/fred-bagley-fonds]

|

| Diary Page, Fred Bagleyto access, click on https://albertaonrecord.ca/fred-bagley-fonds |

Mum got the address of her Aunt Marian, Leona's sister. We drove out to my great-great-aunt's roadside farm and Dad pulled over onto the highway shoulder, and we sat for what seemed like an eternity while Mum mulled things over, hope humming all around me like bees in the sunflowers. “Let’s go on, Roy,” she finally said and the bees fell silent.

That was that. We drove away, not knowing Leona lived only a few miles away, only that she’d remarried and that his name, too, was Roy. Roy Bent.

Three years later we were living in Iowa. My parents put my older sister and me on the train in Fargo, North Dakota. Linda and I were headed for Winnipeg, where an uncle would meet us and drive us out to Lloydminster, Alberta. There we’d spend a few days with our cousins, then take the train to Vancouver for another summer on the West Coast. I didn’t know, ticket in hand that hot, sultry June day in 1969 that my departure point was, in June 1874, our great grandfather’s train terminus, end of the rails.

|

| Mounties sort gear in Fargo, ND |

In Lloydminster, my aunt took Linda and I to an RCMP band concert, front row seats, with our five cousins. We were all musicians. Linda was a flutist, I was a clarinetist, and my single most joy in Ann Arbor, Michigan, had been our middle school band and symphony where we were the recipients of exceptional directing and private study—an unstated requirement if we were to participate. Consequently, Slauson Junior High won numerous awards and today, when I listen to our recordings, I am astonished. I was in “high fiddle” to attend the RCMP band concert.

Two erect Mounties in dashing red jackets and gold braiding stepped out, curtains still drawn, from stage left and stage right, with five-foot long bugles that glimmered in the light. The executed a few fancy steps, faced each other across the space, snapped their horns into position and, without warning, shot the clear tenor tones of “Oh Canada” into the air with such pomp and circumstance that the short hairs along the back of my neck stood up and I was on my feet without knowing quite how it happened. The crowd was not far behind and I bit back tears. I may have lived in the States for four years, but my loyalty was Canadian and I thought at the time it was the sheer excellence of the music and being “home” that had triggered my nationalistic pride and an ecstasy that never, in fifty-five years, has ever been repeated.

|

| Trumpet similar to Fred's |

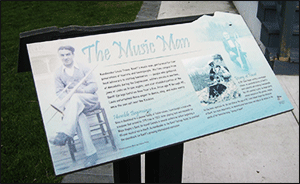

I was thirty and back living on the West Coast when I began my summer treks to Banff and the prairies. In the silence of my missing grandmother, I’d taken to finding what I could of her dad. The Whyte Museum is where I learned of his short stint in Banff, that he’d returned and retired there, and was buried. I also learned that he’d started the Banff Springs Hotel band. Now that was interesting—and some of the pieces began coming together for me. My musical interest for one, but certainly my passion for Banff.

My first trip to Calgary’s Glenbow Museum, however, gave me a start—and then made me mad. I came across a slip of paper in my missing grandmother’s handwriting. Leona had been asked by a Calgary school classroom to submit a list of Major Fred Bagley’s descendents for a 1974 mountie centennial project they were working on. She listed herself, a son and three granddaughters—Leslie, Maia, and Elizabeth. After the shock of seeing her handwriting—she was real!—I allowed the information to sink in. The first thing I noticed was that there was no mention of her first husband Leslie, my Grandpa Les. No mention of her daughter, my mother Shirley Elizabeth, whom everyone called Betty. Certainly there was no mention of us, of me. And then it hit me. The names.

Leona, for whatever reason, had separated from Leslie—yet her eldest granddaughter bore the same name. She’d supposedly abandoned her infant, Shirley Elizabeth—yet her youngest granddaughter carried the baby’s name. And, like her daughter “Betty,” Leona had married a man named Roy. Coincidence? I was beginning to suspect that our unacknowledged and unknown past struggles for recognition; that we have less choice than we think. We are compelled, and the people around us are compelled, to name the past.

|

| Bankhead foundations to learn more, click here |

“You want to know more about Bankhead?” Louis Trono asked when I knocked on his front door later that day, one block off Banff’s main drag. Graciously he invited me in, called for his wife, Joy, to bring us some iced tea for the day was hot. “Tomorrow might be a better day,” he said as we settled in, a lively Italian, eighty-four years old, with slicked back hair and coiled energy. “I have to leave in an hour to rehearse at the Banff Springs Hotel. We play every night.”

“Really?” I said, perking up. “My great-grandfather started that band.”

Mr. Trono plunged forward in his stuffed chair. Iced tea slurped up over the glass brim, down his fingers. He didn’t notice. His eyes were on me. “You’re the Major’s granddaughter?”

I started to ramble about my lost lineage, my search of my grandmother, how I had to content myself with Fred Bagley. Mr. Trono interrupted, smile so big, leaning across the room to shake my hand again. “This is fine! This is a pleasure! Joy!” he hollered. “We have the Major’s granddaughter here!” She came running, a woman twenty or thirty years his junior. More handshakes.

“You knew my great grandfather?” I asked, the bees back in my ears and humming. “You knew him?”

“Knew him? He came out to Bankhead and started the Bankhead band. He taught me how to play the trombone. I was only in knickers. At first he said no, I couldn’t join. I was just a kid. I kept badgering him. He finally thought to shut me up by giving me his old trumpet. But I blew my lungs inside out for a week until I finally got the hang of it, showed up at the next rehearsal, and he had to let me have a shot. I’ll never forget the look on his face. He turned to the big guys and said, ‘This lad is a musician, boys. If the rest of you ever learn to play half as good as—what’s your name, Sonny?—Louis here, I should be so proud.’ But your granddad needed a trombone player—so I’ve played trombone all my life, all over the world.

|

| Fred Bagley 2nd from left |

It was too much for the old man. He flopped back in his chair. Joy fussed. I started to make excuses, asked when I could come back. I, too, needed some time to process the surprise.

“Your grandmother?” he said, pulling out of the shock. “What was her name?”

“Leona.” Bees swarmed through the room, honey in their wings.

“Joy, was it Leona?” he asked, “who taught Marco in grade two?”

Joy pulled out some old school pictures. “Yes, she taught at the little elementary school a few blocks away.” Linda, I thought, thinking of my older sister and seeing my grandmother for the very first time, would be interested in this. Linda was an elementary school teacher, and loved the second grade.

“Are you in a hurry?” Mr. Trono asked, glancing at his watch.

“No, I was going to go over and see if the Craigs would talk to me about Bankhead.”

“Do that tomorrow. I’m taking you to rehearsal, to introduce you to the boys. They’re younger than me, they didn’t know your granddad, but they know of him. Hey, I’ll buy you supper at the hotel. We can visit, and you can stay and listen to us play for the evening.”

Over grilled trout at the Banff Springs Hotel, "Louis" told me that when Bankhead closed in 1919 all the houses were taken into Banff or Canmore, a little town five or six miles east. “I was twelve. My family moved next door to the Major on Beaver Street and summer afternoons he had us boys over to play with his swords. He taught us how to parade. I of course continued my music lessons.”

| Bankhead AB 1904 |

Yet what Louis told me that summer and over the next several years confirmed my growing suspicion that Major Frederick Bagley, despite all reports of his grand, military bearing, could never have called my mother a brat. And if this much of the story wasn’t true?

I started to feel a sense of desperation to find my grandmother. What history begged to be told?

Unbeknownst to me, when the bees fell silent outside my great Aunt Marian’s house, my mother still heard them, and had written her aunts and mother three times for permission to have a copy of her grandfather’s diary. Three times she’d been ignored and I think it was this rejection that stung. Or perhaps these were my own feelings, and I visited them upon Mum in my growing reversal of feelings—love and admiration for Fred, less for Leona. But was this fair?

|

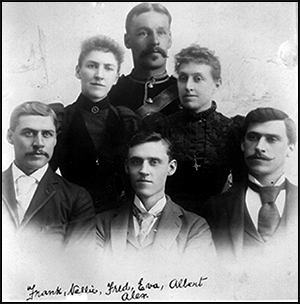

| Betty Goodfellow Wilbee & Dale Bent |

Mum reports that her knees weakened, and she sat down. “You are my brother,” she said.

“Yes. And I have something I think you’d like.”

And so a brother walked into Mum’s life, an uncle into mine, bearing the diary Mum had wanted so badly that she’d risked, three times, her mother’s very pointed rejection.

In the end, it was a death bed sort of confession that brought us Fred Bagley’s diary. Aunt Kate was dying. She called in her nephew, told him there were three letters, that his mother had been married before, that he had a sister, that she wanted their grandfather’s diary. Could he deliver it to her?

He could, and did. That was the good news. The bad news was that his mother—Leona—didn’t want to know about us. This grandmother I yearned for not even interested to know if I existed? Stung, I nevertheless resolved to look at it from her point of view. What was an old woman supposed to do when past became present?

|

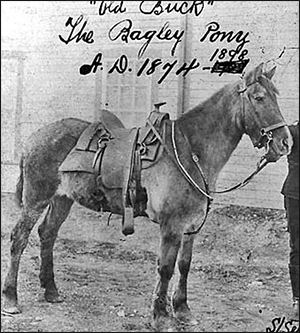

| Buckwheat "Buck", Fred's Famous Pony |

"Buck, as in Buckwheat?" one or the other of us asked.

Once-upon-a-time my younger sister had snuck a cock-a-poo puppy from Bellingham, Washington, onto the plane and taken him as gift to St. Paul, Minnesota, for our mother. Mum had called him Buckwheat—Bucky for short. I thought of the other names we shared—Leslie, Elizabeth, Roy…and now Buckwheat for our pets. How is it possible for a man in 1874 to call his horse with the same name that his never-to be-known granddaughter would give her pet a hundred years later? In the name of all that is rational, how is this possible? I handed Buckwheat’s hoof to Mum, K 1 carved into it, grateful for this curious knowledge.

|

| Banff Train Depot |

“Granny and Granddad had a summer cabin here,” she told me. “Granny often brought me up here from Calgary on the train. Back in those days, the Banff Springs Hotel band came out to greet the trains and to play, always conducted by a kindly old man with white hair with the most regal bearing. I was fascinated by him. I’d dawdle along, staring at him over my shoulder, Granny hurrying me along with a stern ‘come along, Betty.’”

|

| Betty Goodfellow, 8 |

“I thought of that when you first told me about Louis.”

Did Fred Bagley ever sense his granddaughter’s eyes on him as he directed a rousing “God Save the Queen?” Did he ever catch sight of Granny Goodfellow hastening by, anxious to keep them apart? Did he even know they had a cabin a few blocks from his own?

I took my sons to Glenbow when they were twelve and fourteen to help me go through all the photographs. I was getting desperate to meet my grandmother and wanted to get my hands on a picture that could tell me more about her. We found only one of a child—which daughter was this? Conflicting reports of how many girls Fred Bagley had—anywhere from seven to the three I knew about—provided no clue. I asked for a generated photograph of this unknown child looking over her dad’s shoulder. I’d pretend it was Leona.

It was Phil—the same age I was when I first heard my great-grandfather's call—who asked the curator where his great great grandfather’s badges might be located. We’d gleaned enough information over the years to learn there were many. “Probably in someone’s musty attic or moldy basement,” the librarian offered with a grimace. “If you ever find them, let us know.”

Pincher Creek was a name that kept popping up now and then in my research. It was new country for me and I was curious. I was in talking to the curator at the little museum there when the boys came flying into the office, out of breath, exuberant. “We found them! We found them!”

“Found what?”

“His badges!”

Sure enough, there they were, high on the wall, pinned to velvet and encased in glass. To say he had a lot was putting it mildly. A plaque read “ON LOAN FROM THE CONNELLY FAMILY.”

“Who are they?” I asked the librarian.

“A local family.”

“Any relation to the Bagleys?”

“Cousins of some kind, I think.”

I rather liked the idea of having cousins of a sort in Pincher Creek. But it my grandmother I wanted to meet.

|

| Leona Bagley 15 years old |

The spring I turned forty my desperation reached a point of near panic. I wasn’t getting any younger, neither was Leona. I called my uncle; he came up with a plan. I’d fly out to London, Ontario, where they now all lived. He’d introduce me as a family friend; in this way I could at least see her and get to know her. I had my ticket in hand when Phil, now a shocking six feet, four inches tall and skinny as a rail (shocking because no one on either side of his family for as far back as we could trace had ever stood over six feet tall), said, “Mum, if you go meet her as a friend of the family, you’ll never get to meet her as family. And isn’t that what you really want?”

Fred Bagley had been fifteen when he left home. Phil was fifteen. I stared at my son—and tore up my ticket.

I raised my children as a writer and at some point Uncle Dale took to setting out autographed copies of my Sweetbriar series, books on Seattle’s pioneer families, for his mother to find, and to read. Sometimes she asked if he knew if I’d be writing any more. “She’s your granddaughter,” he finally told her at some point, “you can ask her for yourself.” She clammed up. The fifth in the series was released in 1997. I was 45, Leona was 93. It was then that she finally said the words I longed to hear, “I think I’m ready to meet Brenda now.”

It was our common interest in history that slowly built the bridge we needed in order to cross over into each others’ lives. I stepped into a beehive of hurt.

But by grandmother was reluctant to reveal the worst. It wasn’t “nice to speak ill of the dead.” She told me instead of her father—the man we both admired. Fred Bagley, she said, stood six feet, four inches tall; and I found it ironic that it was his six-foot, four-inch great great grandson who enabled me to find her, to be speaking with her.

He was a kindly man, she said. He had a sense of humor and loved a good joke. He had many friends. He treated everyone with dignity and respect, even the prisoners he was assigned to guard. He adored his six daughters, only three of whom survived childhood and hence the confusion. They adored him. “Oh, the good times we used to have,” she said with silver in her laugh and eyes seeing back in time to where I couldn’t go. He abhorred violence, she said. He suffered none to strike them and when a nun made the mistake of taking a whip to Leona’s shins one day in school Lucy May, his wife, promptly withdrew all the girls and settled them elsewhere. The nuns begged that she and Fred reconsider. They did not.

Most certainly, he did not call my mother a brat.

In fact, when she was born, he took the train from Calgary to Vancouver see her—wheeling a wicker pram. Here Mum slept for lack of cradle or crib, and when she was taken from Leona at eighteen months old (not six weeks), he did everything in his power to get her back. The Goodfellows, however, were a formidable foe. My mother it seems was the only battle Major Frederick Augustus Bagley ever fought and lost.

|

| Iamisees / Murderer Big Bear's Son |

View of Fort Pitt, Saskatchewan…I had to accommodate my rate of travel to that of the Indians, who traveled very slowly; consequently this trip of 95 miles with Big Bear’s band took 11 days to complete, while I, on my return trip to Battleford with my men, took only 1½ days to cover the same distance. When I, with the Indians and escort, arrived at a point about half a mile distant from Fort Pitt, but on the South side of the North Saskatchewan River, I received dispatch from the officer commanding Fort Battleford ordering me to return at once to Battleford. After wheeling my men, horses, and wagons about, and starting them on the return trip, I met Ayimeesees (The Wicked One), Big Bear’s son, and stopped on the trail to talk to him. He seemed to be in a very excited state, and doubted my word that there was no serious news from the South, and that Louis Riel had not yet started the expected “Rebellion.” In fact, he went so far as to tell me he thought I spoke with a “forked tongue.” In plainer language that I was blank, blank liar. Following his accusation he seized my horse’s reins, and made a dash at me with a big hunting knife. As my men were by that time at least a mile away on the back track, and, as per my orders, traveling very fast, and, as I was, very foolishly, unarmed at the time, I took the only way out and knocked him down by driving my horse at him and so got away after my men. I am convinced that if he had had a firearm he would have shot me.

Big Bear, Poundmaker, Little Pine, Wandering Spirit…these were men I understood, admired even. But Iamisees? He was a bully and coward. He was selfish, unruly. He sought constantly to undermine his dad. At times I felt sorry for Big Bear, shackled as he was in his old age by such an unworthy son. And to learn that Iamisees had tried to murder my own grandfather? And thus me? I went down to the riverbank and stood looking at the ridge where I’d nearly died before I was ever conceived.

But no one died that nearly terrible day. Frederick Augustus Bagley went on to father Leona, then Mum, then me, then my own daughter and sons, and now my grandsons and granddaughter. He went on to bring the prairies music, and today one can hardly pick up a book on the settling of Canada West or the making of the Mounties without reading of him. Or thumb through an old Scarlet and Gold or R.C.M.P. Quarterly without finding his byline. Or see the Musical Ride without hearing his music. His contribution to Canadian heritage is significant...

|

| Blowing Taps Glenbow Museum |

It's been said in many places that to tell the story of Fred Bagley is to tell the story of Canadian history. Confederated in 1867, the country was but six years old when he rode out as a fifteen-year-old kid to help establish law and order in an area the size of Europe. The Mounties were assigned the task of protecting the Natives north of the 49th parallel from American whiskey traders; and indirectly to warn off the covetous Americans. Fred's story is indeed Canada's--her past and present, for we are Canadian, not American. For me, though, to tell his story is a far more personal overlay of past and present. Grandfather left me the bread crumbs so I could find Leona. And by finding her, I found him.

He once wrote:

"We old ‘originals’ are prone sometimes to believe that we are neglected or ignored by a generation that ‘knew not Joseph' and his works."Yet history does indeed struggle to be told; it struggles because who we were and are is our birthright.