|

| Fred Bagley |

begins not on the Canadian prairie where he made history but in Nanaimo, BC, at the the home of my aunt and uncle, Penny and Dale Bent. My mother and I had been researching Fred as a Mountie. Penny, however, researched Fred's parents, grandfather, and his early life. She'd gone all the way back five generations to Col. James Bland, a Scotsman born about 1793, who, while in the British army, was stationed long enough in Barbados to father Catherine Ann, Fred's mother. And so I drove up through Vancouver to Horseshoe Bay and boarded the ferry for a two-hour crossing to Departure Bay of Vancouver Island to see what information she might have.

__________________________________________

.Below deck and parked, I got a binder of my research from the jeep, hoofed it up three flights of stairs, and hunted down the cafeteria where I began reacquainting myself with what material I had while eating some very bad scrambled eggs and not very good sausage.

My aunt and uncle had retired to Nanaimo, and I found their new abode on a hillside overlooking Departure Bay. Ferries go in and out all day; on clear days you can see Vancouver across the water. It's just about the nicest place to live. But the view paled in my excitement to see what Penny had unearthed.

My great-great-great-grandfather Colonel James Bland had been an officer in the Royal Army, stationed in the British West Indies (now the Bahamas) between 1829 and 1832--leaving behind a toddler and presumably a mistress. Piecing what data we have, a possible scenario emerges. From a birth certificate of one Catherine Ann born in 1830 to a Rebecca Harker, a mulatto, we might well think my great-great-great-grandfather had had a dalliance with a woman of mixed blood. Presumably African. But my DNA says no. I'm about as white as you can get.

There's another scenario.

When Fred and his siblings were all grown up, they inherited their mysterious mother's aunts' "plantation" in Jamaica. These two aunts were Gordons, and the Gordon family were multi-generational British military--which explains why a family of that name lived in the West Indies when James Bland was there. He may well have married a Gordon daughter, which is far more likely than bedding a mistress whose DNA isn't mine. But this begs the question as to why he didn't take his Gordon wife and toddler with him when he retired back to Scotland in 1832. Why, indeed?

|

| Catherine Ann Bland Bagley |

Whoever Catherine Ann's mother was--a mulatto whose DNA isn't mine, or a Gordon, or even some other nameless woman, the Gordons were nonetheless critical to Catherine Ann's upbringing: Her two aunts (whether by blood or close friendship) deeded what was left of their plantation to her children--worth all of $300.

Whoever her mother was, Catherine Ann married Dick Bagley, a lowly Gunner in the British army.

One has to ask why, if she indeed was a Gordon. At the very least protected by the Gordons? This was the Victorian era. Crossing rigid class lines wasn't to be tolerated. The army too had its rigid class structure. An officer's daughter would never stoop to marry a low life in Britain's Royal Army!

Victorian custom aside, why would she give up her luxurious life for the impoverishment of army life in disease-ridden forts? And why did the navy even let Richard marry her? Non-officers were routinely denied wives. Their pay couldn't support it, the work was unforgiving, and living conditions harsh.

The how or why of Catherine Ann and Dick's marriage remains a mystery. Love overcoming all barriers, one might like to think. But as my aunt says, "These weren't romantic people." And if it was love, I think Catherine Ann lived to regret it.

Their first daughter, Evangeline or "Eva," was borne in Belize, Honduras; Fred came next, in Jamaica. The three of his six surviving daughters disputed this for years, one sister saying Barbados, another Jamaica, my grandmother Leona, St. Lucia. She even went to St. Lucia to prove herself right. However, the pertinent documentation had been burned by a fire. I have, however, Fred's baptismal record of Sunday, November 14, 1858, showing that he was baptized at Fort Charlotte, Lucea, Jamaica. An understandable error on my grandmother Leona's part: St. Lucia or Lucea. And so unless Dick was transferred sometime between his son's birth on September 28 his baptismal six weeks later, my great-grandfather Frederick Augustus Bagley was born in Fort Charlotte of Lucea, Hanover County, Jamaica.

Interestingly, Dick Bagley was promoted to Bombardier the day after Fred's baptismal. Had he been serving elsewhere, then, when Fred was born?

Wherever he was born--Fred himself claiming it was Jamaica--his earliest memories were of crying and being shushed with a sugar cane, given him by a black nanny. This suggests his family may not have lived in the barracks but on the plantation where his mother may have grown up. Perhaps, though, the black nanny was as a hired barrack army servant. Whatever the case, Fred wrote that the sugar cane turned him off sugar for life.

The black nanny disturbs me. England had abolished slavery in 1808, but it wasn't until 1838 that Jamaican slaves became fully emancipated—just twenty years before Fred was born. This black nanny would have had little choices for herself back then and, if over twenty-five, could have been deeply traumatized by her own slavery. Attitudes take a long time to change and she was part of a race that had been over-the-top brutalized in Jamaica. I wonder what her history was.

When Fred was two, his father was transferred to Kent, back in England. This is probably when Fred visited his grandfather on the Island of Jersey--a short boat ride away.

For the next eight years—1860 to 1868—Fred's family bounced pillar to post, his mother having babies every two years in a different parts of the country: Frank, 1860; Albert, 1863; Amelia Ellen "Nelly," 1865; Alex, 1867. A year later, in 1868, his dad retired after 21 years in service. Chelsea Hospital housed the retired wounded, the able-bodied were given Chelsea pensions. He became a "Chelsea Pensioner" at half pay, nothing a family of seven could live on, and was described as "39 and 9/12 years old, six foot one inch, fair complexion, dark brown hair and blue eyes" and, remarkably, no marks or scars. My Aunt Penny points out that this means he was never flogged or injured in battle. An amazing accomplishment, given the time. The family moved into 14 Equity Buildings, St. Pancras, Marylebone--one of the poorest slums in London. Charles Booth in 1898 described the Equity Buildings as "a queer little paved cul-de-sac; low one-story two-roomed cottages, with a little wash-house and yard behind...; rents from 6/6 to 7."

Growing up in the army, Fred and his siblings would have enjoyed school. All this stopped when his father retired. Whatever the failings of the British army, it wasn't in the education of their children. Fred and his brothers would have been immersed in horsemanship, music, and the three R's; his sisters in the three Rs plus sewing and household tasks. Now no longer in the army, they would have attended public school...perhaps.

When Dick retired in 1868, family lore says he bought a tavern with some mysterious money of his wife' and burned through it all while Fred and his siblings worked alongside him in the pub. My aunt doubts this; they were too young. However, I've read enough Dickens to know that England's children during this time suffered terribly, especially poor children. They were put to work for long hours, no pay, school a luxury. All the hard work was for nothing. By 1870 Dick was penniless.

|

| Fort Henry |

|

| Pancras Work House, London |

Fred seems to have refused the humiliation and as a 12- and 13-year-old kid he ran free on London's streets—right up to the day when he was brought into the work house prepatory to their departure for Canada.

Who paid for their tickets?Aid societies abounded, trying to deal with the overwhelming poor in England's economic decline. But why would Catherine Ann even want to join a husband who'd left her destitute? She might well have loved him once, but now?

|

| Samartian |

In Kingston, Ontario, Canada, the children once again enjoyed a good education--though at fourteen years old it ended. Fred joined Kingston's Battery "A" as a bugler and enrolled in the gunnery school. When recruitment notices for a newly formed Mounted Police Force to police the Canada West went up, his life changed--and he became the Mountie who helped shape Canadian history.

Not that easy, though. He was only fifteen; you had to be eighteen. He hightailed it down to the recruitment office, and lied. Good plan, but he ran into the commandant of his school—Col. French. Worse, French went round to his house to report him to his father and, according to some reports, there was quite the row.

A self-confessed student of James Fenimore Cooper, Fred yearned to save the Indians out west from the dastardly American whiskey traders and envisioned himself "hobnobbing about with dusky Indian princesses."

In part, he was running away from home. Dick was a harsh man. To punish his boys, he took them out to the gym and boxed them into defeat, then beat them with a belt. Around the girls he managed to keep his fists to himself; nonetheless, they feared the lash of his tongue. So this must have been a hard fight. Finally Dick acquiesced. "Go ahead and take the lad! He'll get over his fascination for buffalo and redskins in short order, I reckon. If nothing else, it'll make a man out of him. But on one condition," he added. "He can only enlist for six months."

The Force pulled out of Kingston in June, 1874. Catherine Ann bid her oldest boy, not yet sixteen, adieu amidst all the fanfare, reminding him to say his prayers each night. She gave him a gold watch and chain and a diary that helped me find him a hundred years later.

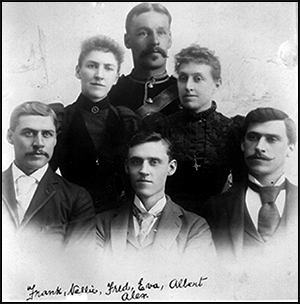

Poor Catherine didn't see him for another fourteen years. The occasion called for this remarkable photo with Fred with his siblings. He didn't stay long and was soon back on the Prairie.

_________

My quest isn't over. Looking for my missing grandmother Leona, I found Fred Bagley. I also found his parents and much mystery in Jamaica. But what about the children of Fred's other daughters? Leona's sisters? My cousins?

No comments:

Post a Comment

If you'd like to comment, I'd love to hear from you.